Alcohol and health: is there really no safe level of drinking?

I’m writing this with a crisp glass of verdejo in hand, curled into a worn leather armchair in our Cornish holiday cottage (after some negotiation with the dog). It’s a welcome reward following a day at the beach, where the idyllic photographs belie the effort required to ensure nobody gets too hot, too cold, or swept out to sea. So many of us use a drink at the end of a long day to relax, to celebrate our joys and forget our woes. It might act as a tonic for the soul, but is even one glass a day damaging our health?

It is according to the authors of a recent study. A few months back the headline “There is no safe level of alcohol consumption” popped up on my BBC news app. With flashbacks to that terrible day when the World Health Organisation declared bacon a carcinogen, I quickly checked the paper to see whether the data supported this bold claim. To my considerable relief, the evidence really didn’t justify abstention from alcohol (in my opinion). Let’s take a closer look.

How was the study performed?

This study was a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis where data from nearly 700 projects were merged to estimate global alcohol consumption and its impact on health. The consumption data was based on “self-reported” intakes which can be notoriously unreliable; I doubt I’m alone in knocking a few drinks off my total when put on the spot. To overcome this the investigators attempted to validate the drinking estimates by comparing them to alcohol sales records and making adjustments to account for tourism and illicit production. They used the pooled data to estimate the influence of alcohol on the risk of developing several adverse health outcomes associated with drinking (but not exclusively; teetotallers get them too). These included diabetes, heart and liver disease, tuberculosis, various cancers and injuries.

What were the findings?

The amount of data in this study was enormous. Rather than discussing all the findings I’ll focus on the major claim of the paper, that there is no safe level of drinking.

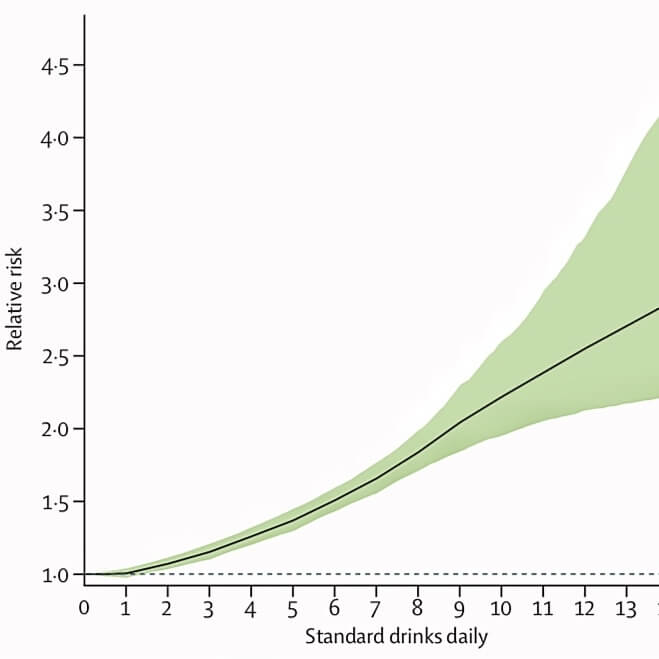

The graph above shows the risk to health from daily alcohol intake, relative to abstinence. The black line shows the average, and the green area represents the level of uncertainty. In this graph, the risk of becoming ill or injured without the influence of alcohol is represented as 1 (dotted line) and any additional risk caused by alcohol is shown relative to this. For example, we can see the risk of getting sick if you have 9 drinks a day is 2, which is double your risk if you never drink a drop. Clear? Well, not especially. We don’t have any idea of the actual number of people getting sick from boozing, and how many of them would have become ill anyway. What if 1 in every 100,000 lifetime abstainers became sick, and twice that, 2 in 100,000, developed an illness after 9 drinks a day? That would indicate a very low level of risk.

The original paper didn’t report the absolute values but a later press release set it out more clearly. It stated that out of 100,000 adults, 914 would develop a (“alcohol-related”) health condition in one year without any alcohol exposure at all. An additional 4 people per year, 918 out of 100,000, would develop a disease if they had one drink per day. That’s one extra health condition per 25,000 light daily drinkers and represents an increased risk of 0.5%.

How much booze are we talking? Prof David Speigelhalter of the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication succinctly put this into context. The study considered one drink to contain 10 g alcohol, roughly the amount in a G&T or small glass of wine. One daily drink amounts to 3650 g alcohol a year. A 70cl bottle of gin contains 224 g of alcohol, so one drink a day would total around 16 bottles of gin per annum (3650 g ÷ 224 g). Therefore, 25,000 people would each need to drink 16 bottles of gin over a year in order for one of them to develop an alcohol-related health problem. That’s 400,000 bottles of gin, causing one health condition.

What about two drinks a day – 20 g alcohol? The study found that an additional 63 people a year (977 in 100,000 or roughly 1 in 1600) would develop a health problem with this level of drinking. That’s 7.3 kg alcohol, or 32 bottles of gin, per person, per year. One extra health problem for every 1600 people consuming 50,000 bottles of gin.

Is there really no safe level of alcohol?

In calculating the overall risk, the authors estimated the number of daily alcoholic drinks that minimises health loss was zero, with a 95% confidence interval of 0 – 0.8. This is a statistical method showing that if you calculated risk in multiple similar sample populations, 19 times out of 20 (95%) the true value would lie between 0 and 0.8 standard drinks a day, or 0 – 8 g alcohol per day. Put another way, the results indicate it is quite possible that drinking up to 13 bottles of gin a year (ideally not all at once) will do you no harm at all.

To be clear, I am not saying that alcohol is benign, and I don’t mean to minimise its impact on well-being. It is incontrovertible that alcohol is correlated with significant global illness and death, as this and many other studies show. Alcohol can and does ruins lives, and I’m aware that my experience as a privileged member of the middle classes who occasionally gets tanked on fizz is a far cry from the misery many people experience as a result of alcohol, or someone who misuses it.

Of course, we should all be mindful of our alcohol intake and the potential risks of overindulgence. However, to me, the findings of this study don’t support the alarmist headlines. What these data really show is that being human is inherently risky, and a light alcohol intake is unlikely to cause harm to most people. To conclude from this study “there is no safe level of alcohol consumption” is, in my opinion, taking the piss.